We as a society devour our news in snippets. We demand answers to pressing issues without having the decency of patience. To indulge in a memoir is too time-consuming, so we instead settle for just the juicy details. We deploy journalists and reporters to get to the heart of a situation without care for the precision and time they must denote in order to retrieve the desired information. We rush them into interviews where they must act like vultures, picking at their subjects for meat. Subtlety and nuance aren’t allowed in this metaphorical bloodsport.

Fittingly enough, this is also how we remember our past. Not with the same apathy, but the same approach. As we piece together our past events, both good and bad, we do so in snippets. Nobody recounts their entire life story in their head, but cherry pick the moments at their most impactful. We even unintentionally dress up the events to fit our perspective, at times altering minor details without noticing. Maybe it’s to justify our mistakes, the benefit of hindsight seeping into our subconscious and altering our past to put us at ease. I’m sure a professional psychologist would have a clear-cut answer for this phenomenon. I myself just have rambling, for that’s what a writer sometimes tends to do.

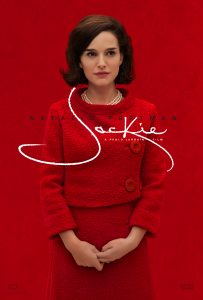

Both the way we intake our news and reflect on our past is on display in Pablo Larraín’s “Jackie.” He deconstructs Noah Oppenheim’s mostly straightforward screenplay to match the tendencies of the human mind. The film is framed as a lot of historical biopics are: an interview with the prominent figure as a way to jump to important moments in their life. Some are widespread, covering the bulk of their lives, while others are more focused on one important date. “Jackie” is the latter, focusing on the assassination of John Fitzgerald Kennedy (Caspar Phillipson). More specifically, the aftermath and how it affected his wife, First Lady Jackie Kennedy (Natalie Portman).

The vulture is only referred to as The Journalist and is portrayed by Billy Crudup. He comes across as a victim of the machine, awkwardly asking searing questions of Jackie in order to spice up his article. She too is a victim, a human being reduced to a mere public figure without time to grieve. She is constantly given condolences from others, but feels not their compassion. By the time this journalist strolls along, she is dismissive and distant. She demands she be allowed to edit the article to best meet her perspective, as others that have been published have been skewed. As the interview goes along, she slowly lets her guard down, sensing that this journalist takes no pleasure in her pain. He stumbles over his words, their intentions mistaken as pithy advice. He states that the country deserves to hear Jackie’s story, but the hesitation in his voice states otherwise.

The way in which we remember our past is presented through Jackie’s perspective. She tells her side of the story sporadically, skipping back and forth from the beginning and end of the assassination. She recounts conversations with journalists and congressmen that had her defending her erratic spending. The money was raised herself as she felt the White House deserved art and history to adorn its walls, not just invisible actions. She feels the need to defend herself constantly as her position as one of the people is always in question. Even when Crudup is not pressing her about this, she misinterprets his questioning as such.

As for the assassination, its arrival is blunt. It is forced out of Jackie, a reflection of our animalistic desire to get to the car wreck of an autobiography first. Its replication is gruesome, the deafening sound of the gunshots piercing the ears. An overhead shot shows the horror and immediacy of the assassination in gory detail, with the focus more on the reaction than the physicality.

Jackie feels the need to justify her actions following the assassination, such as why she felt the need to remain in her bloody outfit and walk her children through the press as opposed to sneaking out the back. She wanted the world to see the damage done, hoping the assailant(s) will take notice and feel remorse. One wonders if it played out that way or if she’s slightly misremembering the events to appease her worries. At one point, she unknowingly puts her children in danger, lashing out at Bobby Kennedy (Peter Sarsgaard) for concealing the information from her. Was Bobby truly to blame or is she afraid of her own mistakes nearly costing her?

A friend of mine questioned Natalie Portman’s portrayal of Jackie Kennedy. He found it to be good, but it felt slightly inauthentic. He wondered if she was simply putting on the act that Jackie herself did in public or if that was who she truly was. I found that to be brilliant on Portman’s part, as it perfectly complements the tone of the film! We never truly get the sense that she’s being completely honest, whether that be intentional or a side effect of grief. Even her (uncomfortably framed) conversation with a priest (John Hurt) comes across more like therapy than a confession. Any possible nuggets of truth are questionable, the ones that seem legitimate feeling so because she retracts them.

Framing the film in this manner was a smart move on Pablo’s part, as the formulaic aspects of the biopic feel veritable. Mica Levi’s overbearing score resembles that of Greek tragedy, but actually complements Jackie’s mindset. It is known that she is a lover of the theater, “Camelot” festering in her brain following the assassination. It only makes sense that she recalls her most tragic moments with an equally tragic score.

Occasionally cutting to scenes in which Jackie has to deal with her children are purposely frank to supplement the stark nature of journalism. The drama in these scenes feel forced, reliant on the heartache of fatherless children to drum up sympathy. This is purposeful as it is symbolic of how society gathers these moments: straight and to the point. Forget gradual empathy; they just want the details. Quick glimpses of sad children offers brief sympathy to justify their overall indifference to the situation.

“Jackie” is a rather cold biopic centered on a significant tragedy. It is not as deep and detailed as other films on the assassination, but that’s because it’s not about the assassination. It’s honestly not even about Jackie; she is but a mere pawn of a psychological examination. The former First Lady is chosen because her tragedy is well-known, her depression the perfect guinea pig to mine commentary from. It is not without respect to her, but strangely out of compassion.

Final Rating: A