Deborah Lipstadt and David Irving are one in the same. Both are historians driven by their passionate belief that their reports on history are fact. The former shares the same belief as many in that the holocaust did indeed happen, while the latter denies its existence due to lack of sufficient evidence. Both have devoted their lives to researching their cause, the former denouncing holocaust deniers for misrepresenting opinion as fact. The latter fervently believes his research is fact and accuses the former of tarnishing his good name via derogatory comments and dismissal. A defamation lawsuit ensues.

“Denial” is indeed a dramatic recreation of the Irving v Penguin Books Ltd trial, but its focus is not on courtroom theatrics. The film is wisely a character study of both Lipstadt & Irving, digging into their mindset to mine drama. The attention is more focused on Lipstadt, not so much because she’s the protagonist whom penned the book in which David Hare’s screenplay is adapted from, but because her growth mirrors the message of the film. The message is in staying true to yourself, even if that means sacrificing your own moral beliefs. That silencing oneself isn’t an act of cowardice, but intelligence in the face of certain adversity. I think back to a Mark Twain quote: “Never argue with a fool, onlookers may not be able to tell the difference.”

It is a quote that Deborah Lipstadt has lived by, hence her refusal to debate with any denier. To her, denying the holocaust is the same as believing the sky is green and the grass is blue. It is nothing more than an inaccuracy disguised as an opinion to hide the misfortune. In the case of David Irving, she believes him to be a racist, anti-Semitic distorting history to favor his warped sense of reality. These accusations in her book ignite the lawsuit, which takes place in the United Kingdom at the behest of David Irving. Unlike in America, there is no presumption of innocence and Lipstadt must prove her accusation to be true to clear her name; not Irving proving her accusations sullied his reputation.

This is where the character study comes into play. Director Mick Jackson carefully streamlines the trial and investigation through the emotions of both the plaintiff and the defendant. We see Irving working his magic on the sidelines, playing victim to the press and making a fool of Deborah in public. He whips up clever catchphrases such as “No Holes, No Holocaust” to drive home his message, ultimately pecking at Lipstadt’s soul. He’s prying on her compassion to goad her into debating the holocaust, going against both her morals and the trial itself. He is using the defamation lawsuit to give credence to his agenda.

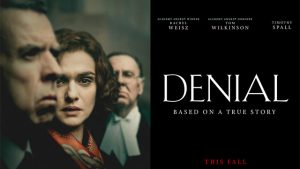

It is in the casting of Rachel Weisz and Timothy Spall where the true brilliance of “Denial” is on display. Both take to their roles splendidly, embodying their counterparts with ease. Weisz carefully exhibits Lipstadt’s tenaciousness and arrogance with benevolence as to show her as human. This goes a long way in making her growth authentic and endearing, showcasing how her beliefs guide her to error. Her denial of a holocaust denier’s belief being given even the slightest of credibility nearly sinks her case. Her compassion for the survivors blinds her to her opponent’s war tactics, causing her to reject the studious workings of her lawyer, Anthony Julius (Andrew Scott), and libel lawyer, Richard Rampton (Tom Wilkinson), as cold-blooded. This performance goes a long way in developing tension within the legal practice, in turn making what could be tedious into a riveting affair.

Then there’s Timothy Spall, who comes close to chewing the scenery as David Irving, but shows enough reserve to do his counterpart justice. He plays up Irving’s tactics as the slimy deceits as they are, but never makes it naturally villainous. One truly believes that Irving buys into what he’s selling. He’s not out for profit but recognition to bolster his self-efficacy. This desire has twisted his sense of reality, causing his research to follow suit (as shown in the radical changes of “fact” throughout his reports). This adds an extra dimension to his actions, not pigeonholing them as mere political chicanery, but an unbeknownst psychological disorder.

Lipstadt almost falls into the same psychological trapping, but is able to avert them via her open-mindedness. Irving feels prosecuted against by society, hence his refusal of a lawyer, acting as his own. This is his downfall as he has nobody to call him out on his shortcomings. This stunts his growth, a possible side effect of his psychological disorder. Deborah curbs this by working alongside her legal team, only jeopardizing it thanks to her altruism. Irving never once exhibits such compassion, his selfishness being his own downfall.

Mick Jackson’s confidence in the character study helps bring the court case to life. He avoids the pratfalls of true story adaptations, only on occasion succumbing to needless emotional manipulation (such as unnecessary imagery of concentration camp victims and random asides from the legal team on the emotional merits of the Holocaust in modern times). The devotion to character development and accurate depictions of legal proceedings is a tricky one, as both can be seen as monotonous. They are engrossing because they’re guided by relatable emotions and a spellbinding subject matter. This film does for legal proceedings what “Spotlight” did for journalism: presented it with precision and reinforced it with humanity.

Final Rating: A-