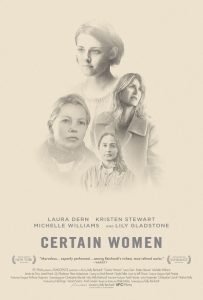

Laura Wells (Laura Dern) sits uncomfortably in her law office in Livingston, one of two hostages including a beefy, kindhearted security guard. Her captor is her client, Fuller (Jared Harris), a blue collar man whose life has spiraled out of control. He’s lost his wife and his court case involving a workplace injury, leaving him with nothing but a shotgun and a broken heart. He confides in Laura, meaning her (nor the security guard) no harm. He’s only turned to drastic measures as a last ditch effort, foolishly thinking the cops will believe his lawyer is held at gunpoint in the front as he sneaks out the back (they don’t, of course). Laura looks on perplexed as he’s arrested and put into the back of a squad car.

Cut to Gina Lewis (Michelle Williams) jogging through an isolated forest. Her destination is her new home, resembling a fancy tent as it’s still under construction. Her husband, Ryan (James Le Gros), waits patiently for her, entertaining their despondent daughter, Guthrie (Sara Rodier). The couple drive up to the home of Albert (Rene Auberjonois), a fragile old man who owns a sandstone of great interest to them. Their acquisition of said sandstone is awkward and stilted, Gina feeling as if her husband is undermining her just as much as he does with Guthrie. She is painted as the bad guy in both occasions, detaching her further from life.

All the way down in Belfry, meek law student Elizabeth Travis (Kristen Stewart) stumbles into town to teach a law class of minuscule attendance. She is not prepared to teach, still learning the material and finding her groove as a teacher, but is determined to prove herself. Her desire to prove her upbringing wrong leads her to mistakenly take this position four hours away from her residence. The bags under her eyes tell a story all their own, one that Jamie (Lily Gladstone) is enraptured by. She is not a student but a lonely ranch hand, dropping in on Travis’ class out of curiosity. The two strike up a friendship, one that the latter craves more from. The pressures of the position get the best of Elizabeth, causing her to relinquish her class to another instructor and, unintentionally, causes a rift between her and her newfound friend.

All three of these stories, adapted shorts from Maile Meloy’s collection, “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It,” interconnect ever so briefly. They don’t need to, really, as their themes play naturally into one another. All are centered on strong, independent women trying to make it by in small-town America. The way in which their lives are intertwined is quite clever in its subtlety, even the most ardent of reasons coming across tranquilly.

The structuring of the stories, however, causes a disturbance. Gina Lewis’ tale is pigeonholed between two superior stories, causing hers to falter in comparison. There is sound reasoning behind her placement, seeing as how her predicament is coyly hinted at in Laura’s account, but that predicament’s impact could’ve still been felt had the stories been switched. Gina’s is so quiet and reserved that it’s bludgeoned by following the weighty hostage situation. Gina’s detachment infects the viewer but not in a positive way, nearly losing me after the film’s hot start. Elizabeth’s narrative is similar in tone, but comes across more powerfully due to its endearing idiosyncrasy. While Gina’s plight may have deep implications, it doesn’t resonate as strongly due to its awkward positioning. Placing it first may not have alleviated its downfalls fully, but the limp nature may not have been as off-putting.

All three stories are paced the same. Kelly Reichardt utilizes a slow burn approach to unraveling the stories, as she did in her western, “Meek’s Cutoff.” The methodical approach was more complementary to that film, matching the peaceful atmosphere of the Oregon Trail. While it is befitting of the quaintness of small-town America, it at times undersells the severity of the situations. It can be as limiting as it is inventive, grinding the film to a halt when it needs to be picking up steam. Again, it is the Gina narrative that suffers the most from this approach, despite being the best suited for it. Elizabeth’s feels in line with the pacing, whereas Laura’s plays around with it for both comedic and dramatic effect. The bombastic tone of the events is juxtaposed wonderfully to Fuller’s lethargy! He is not a threat but a peculiar nuisance, as is the life that entraps Laura. Gina’s story, on the other hand, feels flat in comparison.

Reichardt’s direction is so relaxing and intuitive that it’s hard to resist. Even during the direness of Gina’s struggles, the sedative view on life is strangely intoxicating. The cinematography by Christopher Blauvelt is so beautiful in its simplicity, capturing the essence of life in its most dormant of state. The never-ending hills coated in snow, the playful disposition of farm animals, and the soothing atmosphere of the forest typify the deeper meaning of life on display. Jeff Grace’s hushed score only furthers this. If nothing else, “Certain Women” is a gorgeous film to behold!

Two-thirds of the film connects as planned, with Laura and Elizabeth’s accounts resonating soundly. They are as engrossing as they are poignant, touching upon the sexism that still encompasses the world subtly and wisely. Elizabeth’s is more hidden, brought about by life’s expectations for her given her mother and sister’s placement as underlings. Laura’s is blunter, coming in the form of Fuller accepting his loss after hearing it from a man. His dismissal of Laura’s opinion justifies her explosive reaction, blatantly stating she wouldn’t have gone through this eight-month ordeal had she been a man. On the nose for sure, but tenable. Gina’s, on the other hand, is too forced. Albert uncharacteristically assumes that she works for her husband, not the other way around, only stating so to drive home the message. It had already been established in tone, therefore unnecessary to be so forthright.

I hate to assault the Gina narrative so much, as it’s not an entirely flawed production. It’s just that it’s so rickety that it nearly causes the film’s structure as a whole to crumble. It’s almost unfair to the story itself to be placed between two robust tales. It isn’t weak enough to dismantle the others, but is so to dismantle itself.

“Certain Women” connects where it counts, with Reichardt’s determined direction keeping it afloat during rockier sails.

Final Rating: B