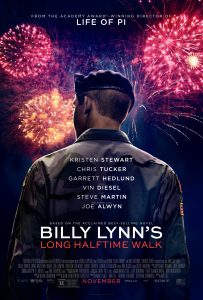

I understand the message of “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk.” It’s hard not to, seeing as how bluntly Ang Lee drives it into our skulls. We as a nation do a great disservice to our soldiers by taking their hardships and making it into our own. Hollywood buys up the rights to each heroic war story, churning out jingoistic tearjerkers to comfort the masses on the home field. In return, the soldiers themselves are trotted out on talk shows and sporting events to continually be congratulated and thanked for their service. For a brief period of time, we treat them as celebrities, until our short attention spans get the better of us and leech onto someone else. We act as if we truly care, but show our true colors when we don’t get something out of the deal. If profitable gains aren’t met and/or the selfish vindication has been fulfilled, we drop our act like a bad habit.

Making a film in which is financed by Hollywood with the intent to shame said process seems kind of redundant, doesn’t it? That’s the question that’s been plaguing me since I walked out of my screening of “Billy Lynn.” It’s a question that harried me throughout the screening, actually. While I understood and accepted the message being dished out, I took issue with how hollow the experience was. Again, I understood that was the point, but struggled with the notion of its futility. I kept thinking how ironic it was to criticize Hollywood for making hollow films about true, harrowing events whilst making an intentionally hollow film to illustrate that point.

My biggest struggle in acceptance was dealing with the fact that the message contained in “Billy Lynn” isn’t that groundbreaking. Numerous films, television shows, books, and political debates have broached the vanity of jingoism. This film itself is an adaptation of an acclaimed satirical novel written by Ben Fountain, with said satire not translating well to Jean-Christophe Castelli’s screenplay. Castelli dispenses the message as if it were unheralded. I was expected to be shocked and outraged as I watched the media exploit the soldiers, and appalled at the snide remarks by drunk football fans (such as the one making crude homophobic remarks). I was meant to be astounded at the discovery that the adulation a cheerleader by the name of Faison (Makenzie Leigh) had for Billy Lynn (Joe Alwyn) was a result of being starstruck, not true love. On the contrary, I knew of these revelations going in, stripping the impact altogether.

Not helping matters is the overt dialogue, spelling out the message entirely. Albert (Chris Tucker), the agent trying to strike a movie deal for the Bravo Squad, explains in full detail the bastardization of Hollywood adaptations. He holds the audience’s hand in explaining how the movie industry creates moments out of tragedy, pillaging the uplifting moments and trashing the reality. He explains how Billy’s affection for Faison is causing a rift in his crew, just as it would in a classic Hollywood love story. He nearly out-and-out states that our perceptions of reality are based upon storytelling conventions, with Hollywood being the biggest culprit. Considering how on-the-nose this film was, I wouldn’t have been surprised had Albert looked directly into the camera and told the audience that they’re being manipulated. Maybe that excessive of an approach would’ve worked out in the long run.

Also the victim of blatant discourse is Norm Oglesby (Steve Martin), the owner of the Dallas Cowboys. He has invited the Bravo Squad to perform alongside Destiny’s Child during the Halftime Show, a not-so-subtle commentary on the disillusion of hero worship. He starts out kind and welcoming, then slowly shows his true colors after lowballing the squad on their motion picture deal. It’s not enough for the act to define itself, but Norm has to “level” with Billy and his commanding officer, Dime (Garrett Hedlund), explaining how their story is America’s story and that something is better than nothing. Again, I am surprised the film didn’t become self-aware and have Norm look into the camera and state, “I’m screwing these guys over because I’m a greedy asshole!”

Ang Lee utilizes a flashback narrative to juxtapose the realities of war with society’s warped perceptions. Normally, I’m opposed to such a cheap tactic, but I found the execution of it to be ingenious. The flashbacks are symbolic of PTSD, striking Billy at inopportune times throughout his patriotic grandstanding. Quick glimpses of his immaturity and short temper at the outset of his training, mixed with the sophomoric antics of the Bravo Squad, highlight the contrast of perfectionism we bestow upon war heroes. We reject the flaws that make them human, converting them into false idols. When they act as human as we do, we hypocritically turn our noses down at them.

As football players and everyday citizens pick Billy’s brains for war stories, they pervert his reality into their audacious fantasies. Lynn’s explanation of killing a man is cold and honest, describing it as surreal. As he explains the emptiness of the situation, he notices the disconnect in the listener’s eyes. To placate it, he relates it to the footballer’s tackling the opposing team, tricking them into thinking it’s an adrenaline rush of the same variety.

The flashback narrative only goes so far, helping the production limp to the finish line. It shortchanges the weight of Billy’s struggles to cope with his distraught sister, Kathryn (Kristen Stewart). She represents the radical left, believing the war to be a profiteering scheme on the part of the government for oil. She desperately tries to convince Billy to escape his imprisonment, going so far to contact a doctor to give him a formal release. Her attempts are to no avail, as he feels he owes it to his country and his fallen comrade, Shroom (Vin Diesel), to serve. The underlying theme of soldiers being astray at home, only feeling comfortable in battle is unfortunately feeble as a result of these shortcomings. This is when the flashback narrative is representative of its cheap nature.

I did wonder if reorganizing the structure of the narrative would’ve aided in elevating the drama. Showing the harsh reality of combat in the first act may have endeared the audience to the squad’s detachment, as opposed to it being a revelation in the finale. As society’s warped sense of reality begins to unravel, we would feel as disengaged as they were. I ultimately decided against this approach, seeing as how it would diminish Billy’s slow realization.

I did also wonder if seeing the film in its proper fashion would’ve propelled the experience. It’s the first feature film to be shot entirely in 120 frames per second, giving the film an intensely high resolution. It has been reported that only a select few theaters in the world can accommodate the framerate fully. I know for a fact my local Regal theater is not one of the select few. I don’t think it would’ve made much of a difference, but I’d be curious if a proper screening, as it were, would heighten my opinion at all. As it is, I did find the film to be gorgeous and magnetic! The cinematography by John Troll is crisp and exquisite! Whatever the complaints may be, I was not bothered in the slightest by the framerate.

Nevertheless, the accelerated framerate would only carry the film so far. “American Honey” wasn’t successful simply because the pan-and-scan ratio complemented the isolated world of the protagonist, but because it was backed up by compassionate direction and a sharp script. While Ang Lee has the best of intentions, his direction is rather flat, relying on underwhelming revelations and a painfully overt script. I understood and appreciated his hollow approach, but found it to be fruitless in the end.

Final Rating: C