If Tim & Eric made a grindhouse flick, the result would be “The Greasy Strangler.” The film is defined by its exaggerated humor, taking the most mundane and/or immature of tasks and prolonging it for comedic effect. The laughter induced is from the bizarre holding pattern of the joke, such as when the father and son call each other bullshit artists repeatedly, pausing for maximum effect. This style is even implemented subtly, such as characters staring at each other just a tad longer than usual. It’s not just that the film stops dead in its tracks, but the characters do to. Again, calling back to the father and son, there’s a benign scene involving breakfast being served that lingers just a hair too long. The sight of seeing the father and son staring satisfactorily into each other’s eyes, the creepiest of grins draped across their face, commands the most uncomfortable of chortles.

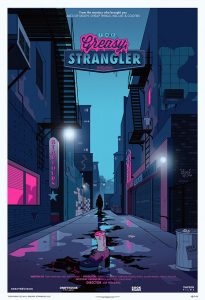

The father and son are Ronnie (Michael St. Michaels) and Brayden (Sky Elobar), and to call them eccentric would be an understatement. They live in a decrepit house in Los Angeles, with the rundown exterior resembling a palace compared to the grimy interior. Dust bunnies claimed this home long ago and they’ve gone running for the hills ever since the father/son duo sauntered through the halls in nothing but the tightest of underwear. No attempt to clean up after the dust bunnies’ departure has been made. The only activities to be had here are sleeping and cooking; I highly doubt the shower gets much usage (though Ronnie is seen brushing his teeth in the nude at one point, one of many uncomfortable sequences).

Brayden does the cooking, usually poorly to Ronnie’s standards. He loves grease as much as he loves disco and women, demanding his food to be engulfed in it. If you’re thinking this means he’s the Greasy Strangler, then you’d be correct. The entire joke surrounding the gimmick is how obvious it is. Ronnie’s love of grease spells out his secret identity, his outbursts of denial to nonexistent accusations not helping matters. Thankfully for him, everybody in this subsection of Los Angeles are clueless buffoons who couldn’t put together a puzzle if all but one piece was left. The humor is meant to come from the obviousness, not the joke itself.

Comedies like this don’t tend to lend themselves to feature length, the gag running thin halfway through. Just look at Tim & Eric’s own film, “Tim & Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie,” as an example. It’s not that there’s no effort made, just that obvious, awkward humor runs its course after a while. There’s only so many times I can watch prolonged scenes of gaucheness before I start growing tired. While “The Greasy Strangler” falls victim to this, Jim Hosking shrewdly suppresses the issue by incorporating two plot points to help guide the insanity.

The first involves the Greasy Strangler, placing him in a prototypical slasher. He stalks the seedy streets of Los Angeles at night, striking with furor. All of his victims are those who have slighted him in his normal persona of Ronnie, be it the tourists who demanded free drinks or the hot dog vendor who denied him his beloved grease. His method of choice is strangling, of course, but he’s prone to switch it up every now and again like every good slasher, such as when he drives a victim violently into a vending machine. Another victim has his face caved in with one punch, the end result resembling a Claymation creation being smooshed. Those who fall victim to the strangling have their eyes comically popped out of their skulls, roasted and dipped in grease as a disgusting treat. The best comparison would be to compare this section of the film to that of a Troma title: loud and garish and proud of it.

The Greasy Strangler himself even resembles a Troma character, specifically their mascot, the Toxic Avenger. He’s a mix of him and Swamp Thing, but with even less of a budget. The crude makeup only complements the lowbrow tone, so that’s a good thing. The getup accomplishes its goal in grossing out the audience, though I reckon the sight of Ronnie’s birthday suit (replete with an obscenely unpleasant penis) will turn more stomachs than anything else. Throw in Brayden’s birthday suit into the mix as well (replete with an obscenely unpleasant micropenis).

The other plot point is a love story between Brayden and Janet (Elizabeth De Razzo). She’s his first and only love, his shyness and social discomfort winning her over. There are many scenes in which he coyly tries to flirt with her, the discomfort garnering chuckles. Her admiration for him is almost sweet despite it being encased in such a revolting picture (and I mean that in a complimentary way). It’s a shame to see it succumb to an outlandish love triangle involving Ronnie. It makes sense for it to occur, especially with how heavily it’s hinted at in the outset, but Hosking waits far too long to fully introduce it. It feels out of synch with the story’s structure, arriving after Janet’s rejection of Ronnie and Brayden’s suspicions of his father’s alter ego. I assume that’s the point, to deconstruct the fabric of conventional storytelling and flip it on its head, but the result is underwhelming.

The love triangle is introduced at the breaking point for me, right when the awkwardness loses its trance. While this theoretically would pull me back in, it fails to do so because it relies on the same tropes and humor that I’ve grown tired of. Had it been introduced earlier, I may have been more susceptible to its peculiarity. By this point, it was acting as a distraction to Brayden’s investigation, which opened the door for many possibilities. The only one met is a ridiculously stupid, and therefore ridiculously amusing, scenario in which Ronnie blatantly impersonates a detective to sway Brayden’s beliefs. This includes donning a costume equipped with a phony mustache and those finger blades you’d receive in cereal boxes that resemble plastic Bugles. The absurdity and stupidity of it all was too charming to resist and I wish I could’ve seen more scenes such as this!

While the film revels in stupidity and depravity, it is neither from an artistic standpoint. Jim Hosking is a smart filmmaker, crafting clever comedy from a lowbrow outline. Along with co-writer Toby Harvard, he breaks down the mechanisms of both grindhouse films and trashy comedies, taking what makes them popular and cranking them up a notch. Instead of steamy sex scenes, he fills the film with uncomfortable ones. Instead of vomit-inducing gore, he injects cartoon physics. He’s not lampooning the genres, but ingeniously pointing out true depravity.

The moments in the film that cause one’s skin to crawl are the mannerisms of the characters. Ronnie’s devouring of grease turned my stomach more than anything else. The soundtrack, credited to Andrew Hung, does more to make one unsettled than any gross-out gag. His score is of the upbeat techno variety, but distorted throughout to confuse the senses. Even the casting goes a long way in destabilizing the audience. Michael St. Michaels bears a striking resemblance to Klaus Kinski, whose appearance always elicited chills, whereas Sky Elobar reminded me of Tim Heidecker at his strangest (adding more credence to my Tim & Eric comparison). The two of them alone caused massive discomfort, and I praise them for their brave and unorthodox performances!

Hosking avoids being weird for the sake of being weird, which kills productions such as this dead in their tracks. He admittedly overdoes it during the finale, though that feels more like he didn’t know how to end the film more than anything else (which, again, could be the entire point). He’s more concerned with earning his weird label than just demanding the film be accepted as such. The film plays out like a manic depressive fever dream than a carnival sideshow. It’s because of this drive that the film is as successful as it is. It may hit a wall halfway through, but it’s at least beguiling enough to carry one through until the end.

Final Rating: B