The California desert is representative of Hell on Earth. I, of course, mean this in reference to its part in the horror anthology, “Southbound,” though one could argue a case for reality, as well. In “Southbound,” the desert acts as a desolate wasteland where tormented souls go to perish. Once entered, there is no escape unless one is chosen to enter the Promised Land. If not, any escape is thwarted by a mystical entrapment, the kind where driving straight somehow leads you to the same rundown gas station from which you came.

The desert plays host to five interconnecting stories. The first is of two brothers (Chad Villella & Matt Bettinelli-Olpin) trying to escape their past and current rendezvous in Hell’s California residence. The second involves a band of three girls (Fabianne Therese, Hannah Marks, & Nathalie Love) encountering a strange cultish family after their van breaks down. The third is of a man (Mather Zickel) trying to save the woman he accidentally ran over via the assistance of devilish 911 dispatchers. The fourth has a brother (David Yow) in search for his lost sister (Tipper Newton). The fifth and final chapter is of a family (Gerald Downey, Kate Beahan, & Hassie Harrison) being ambushed in their hotel room by masked thugs. One expects to hear the voice of Rod Serling introduce us to each story, but is instead greeted by an on-the-nose shock rock radio DJ (Larry Fessenden).

The way in which the stories connect ranges from loose to tight. The second story has one of the band girls bleed into the third. One of the demonic dispatchers from that story transitions immediately into the fourth. As for the first and final act, characters from one of them reappear at one point to connect the entire film together. Once it’s revealed whom, the final story loses its tension, as we know exactly where it’s going. We don’t know how it’s going to get there exactly, and I’ll give credit to that story’s writer (Matt Bettinelli-Olpin)) and director (Radio Silence) for staging an out-of-nowhere descent into Hell. Even so, the impact of the final shot isn’t as clever as the producers of the film think it is.

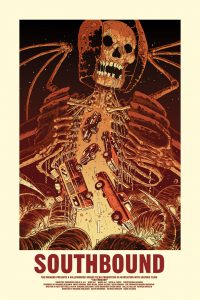

In the background of each story are floating skeletons, acting as the Grim Reaper’s henchmen. When seen far off in the distance, they elicit foreboding dread. When shot up close, they elicit unintentional laughter. The skeletons too closely resemble those you’d find in a cheap carnival haunted house attraction, with only a few tweaks to make them more satanic. They look too corny to scare anyone and almost sink one’s opinion of the film from the outset, as they’re the ones chasing down the brothers in the film’s opening sequence.

The skeletons reminded me of those old shot-on-video horror flicks from the late eighties and early nineties. Filled with great intentions, but marred by a shoestring budget. You admire the tenacity and drive of the filmmakers, but can’t help but laugh at the pithy excuse for a prop.

The difference here is that “Southbound” isn’t filmed on a shoestring budget. If it is, the filmmakers found a way of making it feel otherwise. The film itself is gorgeously shot, boasting slick production values and intricately placed camera angles! Sometimes, it feels as if we’re watching the film through a distorted lens, just as the victims of the desert are traveling through a distorted reality.

Even the special effects are exceptional, barring those damn skeletons! The otherworldly demons in the fourth story are cloaked in impressive makeup, with one creature brandishing razor-sharp claws. The body mutilation of the woman in the third story is realistically gruesome, with her leg barely hanging on by a thread. We wince as we see her bones slowly pop out of place. And the aforementioned descent into Hell in the final act is impressively done via CGI, giving the hokey skeletons an admittedly badass entrance!

As with any anthology film, some stories are better than others. The three in the middle fare the best. Roxanne Benjamin and co-writer Susan Burke create an air of mystery around the family’s intentions for the bandmates that keeps one glued to the screen. David Bruckner uses a sense of urgency and body horror to carry his tale of redemption after a car accident. Patrick Horvath and co-writer Dallas Hallam get to have the most fun, creatively playing around with the deserted town’s demonic denizens in a brother’s quest to save his lost sister. The first and final story, both directed by Radio Silence and written by Matt Bettinelli-Olpin, are the weakest. The first is doomed thanks to those lousy skeletons playing such integral roles, while the last one is tarnished by its connection to the first. Any anthology film, even the bad ones, are smart enough to start hot and end hot, yet “Southbound” does the opposite.

“Southbound” isn’t a bad anthology film, though. On the contrary, it’s quite good! The way in which each story interconnects is pleasing, and all involved do a superb job of creating atmosphere! The California desert is as much of a character as the doomed souls trapped inside of it. That level of intrigue is carried throughout the film, even in the lesser installments.

Final Rating: B