Summer is the time of year where childhood innocence fully blossoms. With the restrictions of school lifted, a youngster has the time and opportunity to let their imagination run wild. Whether it be playing sports out in the park, going for a bike ride, taking a leisurely swim in the local pool, a child has all the time in the world to do whatever their heart desires. Needless to say, it’s the best time of year for a kid.

Summer is the time of year where childhood innocence fully blossoms. With the restrictions of school lifted, a youngster has the time and opportunity to let their imagination run wild. Whether it be playing sports out in the park, going for a bike ride, taking a leisurely swim in the local pool, a child has all the time in the world to do whatever their heart desires. Needless to say, it’s the best time of year for a kid.

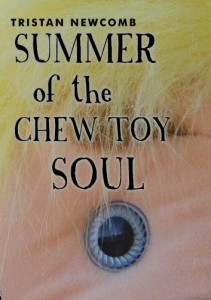

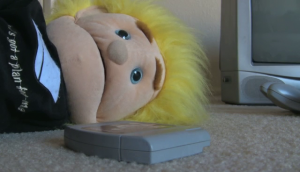

Unfortunately for the titular child in “Summer of the Chew Toy Soul” (who remained nameless, but is portrayed by the puppet Dobo, so I’ll refer to him as such for simplicity’s sake), summer is the worst time of year. His mother has gone away for three months to Spain with her boyfriend, leaving him behind with his alcoholic, abusive and suicidal father (played by writer/director Tristan Newcomb, who also provides the voices for both the narrator and Dobo). Making matters worse is that their apartment is mostly empty and Dobo has absolutely nothing to do.

I mean this literally. His father can barely make it by on his menial paycheck that getting McDonald’s is a luxury. He can’t afford cable or a satellite dish, as he spends his cash on booze. He does a laptop, but keeps it password protected and out of reach from Dobo.

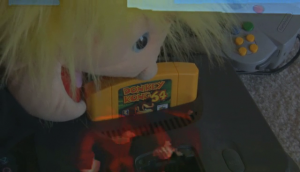

All Dobo wants is to be an online video game reviewer and make millions of dollars in doing so (if only it were that easy). In order to do this, he needs a video game system. His father caves and snags him a Playstation 2 from a thrift store, only for that to be broken. He exchanges it for a Nintendo 64 and a copy of Donkey Kong 64, which delights Dobo. As luck would have it, the expansion pack required to play the game was not attached. Fearing another beating, he avoids bringing up this setback to his father and spends his days lying in a corner.

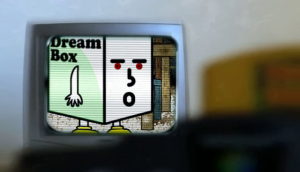

As the days go by, Dobo becomes increasingly bored and depressed. He has no companions, nor does he have any activities to partake in. No television, no video games, no books, absolutely nothing. His only escape is his imagination, which he taps into via physical harm and, sadly, alcohol.

He discovers that, when near the brink of unconsciousness, his mind begins to wander and he’s transported to a translucent dreamscape where he can play Nintendo 64 and evoke his own cartoons. These are frighteningly vulgar and graphic for such a young mind, effectively invigorating the type of heartbreak and dread that Tristan Newcomb was aiming for.

My last foray with this man was “Only Interstellar Pinball Lives Forever”, which also starred Dobo (he’s essentially the spokesperson for Lumalin). Despite his best intentions, I felt that film missed the target completely and never truly captivated me into caring for the characters or Newcomb’s message. I wasn’t lost in the story, but completely lost in what is trying to convey.

Thankfully, I was lost in this movie. Tristan’s message is loud and clear, if not manically depressive (though that’s the point). It’s a heart wrenching film that successfully tugs at the heartstrings and fully immerses your mind into it’s intoxicating visual feast. While the acid trip feel and artsy camera work felt forced in “Only Interstellar Pinball Lives Forever”, it’s right at home in this film.

It lends itself well to the story, as it bounces off the characters perfectly. Both Dobo and his father are in drunken and depressive stupors, which triggers freaky imagery and lightheadedness. You as the viewer partake in this, as many crazy imagery is thrown at you. It’s hard to explain, though I wills state “The Muppet Show” has never been more bizarre.

Many will question the usage of a puppet as opposed to an actual child. Some will see it as a way of saving money, others simply viewing it as a way to avoid having a child partake in alcoholic situations. There are two ways in which I viewed it, with one of them hopefully being Tristan’s intention. If not, by no means was the film damaged. This film is all about the viewer’s perception, just as much as it is the director’s.

My first thought was that Dobo was used as a statement on how the child feels. As the title suggests, he feels like a chew toy being devoured by the world. His father treats him like garbage, chewing him up and spitting him out as he pleases. He doesn’t view him as a human, but a simple chew toy he can take his aggressions out on when he sees fit. Using Dobo reflects this feeling of loneliness and uselessness, as there’s nothing more feckless than a chew toy.

My other theory was that Dobo was in fact this lonely child’s only friend. We all had a toy or stuffed animal that acted as our imaginary friend when we were younger. It was always there when we needed it, always listening to our inner thoughts and feelings. For the majority of us, we had actual friends to confide in as well, limiting the imaginary one’s assistance.

For Dobo, it’s all he’s got. Due to this, his misery is played out through a puppet, since he’s essentially morphed into that. There’s a moment in the film where Dobo is contemplating suicide and visiting his old pets where a collage of photographs plays. In these photos, Dobo is an actual human child, not a puppet. This leads me to believe that the child is acting out his emotions through his imaginary friend.

The ending trumps these two theories a bit. I wasn’t a particular fan of it, as it kind of terminates any outlook the viewer came up with. Tristan doesn’t exactly come out and present his intention, which is a good thing. Thanks to this, my theories still stand, though a stronger argument needs to be made for them. It does also answer a question of mine as to why more information on the mother wasn’t given (though I still would have welcomed that).

Tristan Newcomb’s films present themselves to a niche audience. The mainstream appeal is vastly limited, as the powerful elements and psychedelic direction will be a turn off for many. I know it was for me when it came to “Only Interstellar Pinball Lives Forever”. In the case of “Summer of the Chew Toy Soul”, I was happily a part of that niche group. I felt his message, though still a bit heavy handed in spots, was splendidly conveyed and led to me not only opening my mind to his ideas, but wanting to do so in the process.

Final Rating: B+